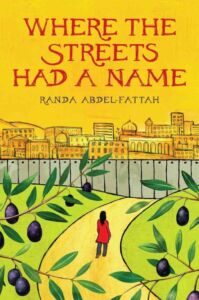

by Randa Abdel-Fattah

Scholastic, 2008

Thirteen-year-old Hayaat lives in Bethlehem, where she is separated from Jerusalem by the security wall constructed by the Israelis against terrorist operations – although the rationale for the construction of this wall is never spelled out in Randa Abdel-Fattah’s Where the Streets Had a Name. Instead, it is described in loaded language as “the ubiquitous Wall, twisting and turning, devouring the landscape, towering over the fields, villages and towns” (122). This, of course, is a distortion, since most of the security fence is an electrified fence, not a wall at all.

Hayaat is strongly attached to her grandmother, her “Sitti,” and when the old woman becomes ill, Hayaat is determined to make the difficult trip back to her grandmother’s former home in Jerusalem (from which she was exiled in 1948), and return with some soil, to give her grandmother comfort and reaffirm her connection with her lost home. This she does with Samy, a boy filled with resentment over his father’s lengthy incarceration by the Israelis; Hayaat says to Samy, “your father’s a hero. Locked up all these years for no reason other than organizing protests and strikes.” (125) – an accusation, like many of Abdel-Fattah’s, that has to be taken with a grain of salt. It isn’t protests and strikes that the Israelis object to – it’s violence and terror.

Because the context underlying the restrictions on mobility depicted in Abdel-Fattah’s anti-Israel screed is never outlined by the author, a young reader will come away from Where the Streets Had a Name with the impression that the Israelis make Palestinian lives miserable for their sport. That the security fence was constructed, and that checkpoints function, to ensure that armed terrorists and suicide bombers don’t enter West Jerusalem to bomb cafés or stab Israelis is never explained. So while it may well be true, as Hayaat says, that “there’s a cloud of humiliation looming over us as the soldiers scold women when they don’t empty their bags quickly enough and order some of the men to remove their shirts and raise their arms in the air” (151), these measures save Israeli lives. Doubtless some young Israeli soldiers and border police are bored, inconsiderate, even abusive. There is a distressing account in the book of Israeli soldiers stationed in a home in Gaza (the book was published in 2008) where they humiliate the father by denying him use of his own bathroom until it is too late. Whether this is fact or fabrication is impossible for the reader to verify. But the IDF would not be in Gaza at all if it weren’t for the threat to Israel posed by Hamas.

Like many of her fellow Palestinian authors, Abdel-Fattah relies heavily on nostalgia for an idealized past to garner sympathy for the Palestinian cause, painting an idyllic picture of the world she inhabited before tragedy struck her family. Sitti describes her ancestral home:

“I lived with my parents and sister in a village on the top of a hill in Jerusalem,” she explains. “To reach our house you had to climb a steep stone staircase” (104).

It is Sitti’s longing for her past that inspires Hayaat to sneak into Jerusalem:

I peer out at the landscape. I want to climb those stone stairs, touch the hills where Sitti Zeynab and her sister danced on their wedding days. I want to tear our papers and identity cards into a million tiny pieces and throw them to the wind so that each piece of me can touch my homeland freely (107).

What Abdel-Fattah fails to tell her readers – and what she herself may not know -- is that the uprooting and dislocation of Jerusalemites in 1948 cut both ways; Jews whose families had lived for generations in the Old City were uprooted in that year. Sima Nightingale’s family had lived in the Jewish Quarter for eight generations when, during the 1948 siege, an Arab sniper on the roof of the synagogue near her family home shot her grandfather dead as he went to fetch the last of his family’s water supply. Puah Shteiner’s family had been in Jerusalem for six generations, ever since her ancestor Rav Eliezer Bergman arrived in the city in 1835. She remembers fleeing her Jerusalem home with only the clothes she was wearing:

[A]fter several days of massive shelling, in which people were killed and injured, the Old City [the Jewish Quarter of Jerusalem] surrendered. At first, on the day the surrender was announced, I was happy. “Now there won’t be any more shooting,” I thought. “We won’t die here, we’ll survive.” But then I went out and saw that people had their heads down. Our Old City had fallen into the hands of the Arabs. We would no longer have access to this holy, precious place. I was seven years old when we were expelled from the Old City.[i]

If Sitti and her family had to flee their Jerusalem home, so did the residents of the Jewish Quarter (the Old City) have to flee theirs, at the command of the Jordanian Army, in 1948.

The book offers a litany of accusations against the Israelis: that Jews who build in Jerusalem are “settlers,” that home demolitions are unregulated, that IDF soldiers shoot a man as punishment for his links to a suicide bomber. All of this makes the Israelis look like brutes who wantonly exercise unchecked power, because nothing is explained: that home demolitions have been extensively debated and ruled on by the Israeli Supreme Court, that the role of the IDF soldier is to arrest, not to carry out punishments, and that there is land that Israeli courts deem legal to build on, and other land on which building by Israelis or by Arabs is illegal.

As proof that her attacks against Israel are untainted with prejudice, Abdel-Fattah offers her readers two “good” Israeli characters, but – given the author’s premise that Israel is imposing unwarranted hardships upon a largely innocent Arab population – in fact the only “good” Israelis are those who oppose their government’s measures. The “good” David deserted from the IDF after observing the misbehavior of soldiers when they took over a house in Gaza. He and Mali describe themselves as “peace activists” who are “on checkpoint watch” and are “against the occupation”(129).

The “occupation,” however, is never explained -- neither how it came about, nor why, from the Israeli perspective, it has persisted since 1967. So young readers are left with the impression that the occupation was engineered by Israel to oppress another people. That under the Oslo accords large tracts of the West Bank are under the control of the Palestinian Authority, which offers considerable local (and quite corrupt) government, is never disclosed by the author.

-Reviewed by Marjorie Gann/April 2, 2025

[i] https://jewishaction.com/jewish-world/history/voices-of-faith-memories-of-1948/

Education Institute

Education Institute